|

An Air Force transport plane flew me and a dozen other Marines to Kyoto, Japan for two weeks of Rest and Relaxation. Kyoto is a beautiful city of Buddhist Temples, Shinto Shrines, and enchanting floral gardens, untouched by the war. Preserving the beauty and history of that ancient city and other national treasures—particularly after witnessing the total destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—may have been one of the reasons for Japan’s surrender during World War II. |

We checked into a downtown hotel, dropped our bags in our rooms and headed down to the lounge bar for a cold beer. I had my usual Coke but didn’t stay long. There was something else I had planned to do while in Japan and it bore little resemblance to what Marines on “liberty” usually do with their free time.

Before my friends ordered a second round, I walked over to the check-in counter and asked the clerk if he knew of a Judo school near the hotel. He didn’t know of any in Kyoto and referred me to the hotel manager. The manager confirmed the clerk’s information. He also told me that there was a famous Judo school in Tokyo, but it was hours away and too far to commute in a train usually so crowded, that just getting on it would be a problem. With less than two weeks to get in any effective practice, it was not a practical option.

“But, there is a police station nearby,” he said. He seemed pleased, even relieved, that he could offer me a possible solution.

“A police station?

“Yes. They have a Judo team. Maybe they can provide the training you seek. They are only a short distance from here.” He drew the directions on a piece of paper and handed it to me.

“Thank you,” I said, thinking that I must learn to say it in his language before I leave Japan.

Early the next morning I walked over to the station. A young officer was sitting behind a desk just outside the entrance. I tried to explain to him what I wanted to do, but his English, like my Japanese, was non-existent.

Before I go any further, I must draw a more complete picture of a scene that, from his perspective, must have seemed strange at best.

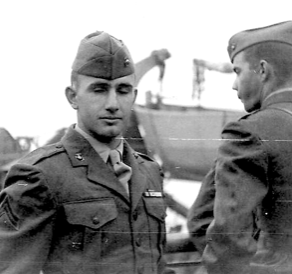

Standing before him, wearing my Marine Corps dress green uniform, with newly sewn-on corporal stripes and a single row of combat ribbons, I literally represented what he and his countrymen probably regarded as the most hated and feared branch of the United States military. It had been less than ten years since the Japanese Army and the U.S. Marines faced each other in the bloody battles of Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Kwajalein, Iwo Jima, Eniwetok, Saipan, Guam, Corregidor, Iwo Jima, and every other island of strategic importance from Hawaii to the shores of Japan. The cost in human lives totaled in the tens of thousands of men and women on both sides.

The policeman in front of me may have been too young to have participated in those battles, but I’m sure he had friends and family who did, and that some of the older men in the station behind him had, indeed, been there and returned to tell their stories.

Even though the horrific images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had to be indelibly imprinted in the minds of every surviving Japanese citizen, he didn’t just dismiss me, tell me he spoke no English, and send me on my way; which he would certainly have been justified in doing. Instead, he escorted me inside and introduced me to the station Chief.

The Chief also spoke no English and immediately called in someone to interpret for us. As soon as he understood what it was I was asking, he swung around in his swivel chair to open the cabinet behind him and carefully pulled out a neatly folded Gi (a white Judo uniform) with a rolled-up black belt lying on top—his, no doubt. He bowed his head as he ceremoniously handed it to me. I tried to refuse the belt—saying something about my being a beginner—but he insisted I take it. I did and respectfully returned the bow. He then called upstairs to summon the Captain of their Judo team.

I caught the questioning look on his face when he walked in. So did the Chief, who quickly introduced us and explained why I was there. The Captain was in his early thirties, stood about five foot seven, and looked to be in remarkable physical condition. He exuded a level of confidence and strength I have sensed in few other men. He never took his eyes from mine as he bowed, and I instinctively did the same.

Minutes later we were in a backroom Dojo preparing to throw each other onto the hard straw tatami mats. We were not alone. At least ten other officers at the station, including the interpreter, had filed in with us, no doubt, wondering what this young American Marine was all about.

My instructor did not teach me any throwing moves until he was satisfied I knew how to fall. So, for the first twenty minutes, he taught me how to safely absorb the impact of a hard fall to either side and to my back. He taught me how to roll over my right and left shoulders to quickly recover my footing and to end up facing my adversary—techniques not unlike those I had learned in four years of high school wrestling. Nevertheless, he would not show me even the basic throws until I could do the falls to his satisfaction.

That first session lasted about an hour and a half. We would get in only seven more before I had to go back to Korea. Despite the short time we practiced together, he was able to teach me sixteen powerful throwing and submission techniques. The interpreter wrote them down for me in Japanese on a piece of paper that somehow survived Korea and the many other military assignments that followed.

Before my friends ordered a second round, I walked over to the check-in counter and asked the clerk if he knew of a Judo school near the hotel. He didn’t know of any in Kyoto and referred me to the hotel manager. The manager confirmed the clerk’s information. He also told me that there was a famous Judo school in Tokyo, but it was hours away and too far to commute in a train usually so crowded, that just getting on it would be a problem. With less than two weeks to get in any effective practice, it was not a practical option.

“But, there is a police station nearby,” he said. He seemed pleased, even relieved, that he could offer me a possible solution.

“A police station?

“Yes. They have a Judo team. Maybe they can provide the training you seek. They are only a short distance from here.” He drew the directions on a piece of paper and handed it to me.

“Thank you,” I said, thinking that I must learn to say it in his language before I leave Japan.

Early the next morning I walked over to the station. A young officer was sitting behind a desk just outside the entrance. I tried to explain to him what I wanted to do, but his English, like my Japanese, was non-existent.

Before I go any further, I must draw a more complete picture of a scene that, from his perspective, must have seemed strange at best.

Standing before him, wearing my Marine Corps dress green uniform, with newly sewn-on corporal stripes and a single row of combat ribbons, I literally represented what he and his countrymen probably regarded as the most hated and feared branch of the United States military. It had been less than ten years since the Japanese Army and the U.S. Marines faced each other in the bloody battles of Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Kwajalein, Iwo Jima, Eniwetok, Saipan, Guam, Corregidor, Iwo Jima, and every other island of strategic importance from Hawaii to the shores of Japan. The cost in human lives totaled in the tens of thousands of men and women on both sides.

The policeman in front of me may have been too young to have participated in those battles, but I’m sure he had friends and family who did, and that some of the older men in the station behind him had, indeed, been there and returned to tell their stories.

Even though the horrific images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had to be indelibly imprinted in the minds of every surviving Japanese citizen, he didn’t just dismiss me, tell me he spoke no English, and send me on my way; which he would certainly have been justified in doing. Instead, he escorted me inside and introduced me to the station Chief.

The Chief also spoke no English and immediately called in someone to interpret for us. As soon as he understood what it was I was asking, he swung around in his swivel chair to open the cabinet behind him and carefully pulled out a neatly folded Gi (a white Judo uniform) with a rolled-up black belt lying on top—his, no doubt. He bowed his head as he ceremoniously handed it to me. I tried to refuse the belt—saying something about my being a beginner—but he insisted I take it. I did and respectfully returned the bow. He then called upstairs to summon the Captain of their Judo team.

I caught the questioning look on his face when he walked in. So did the Chief, who quickly introduced us and explained why I was there. The Captain was in his early thirties, stood about five foot seven, and looked to be in remarkable physical condition. He exuded a level of confidence and strength I have sensed in few other men. He never took his eyes from mine as he bowed, and I instinctively did the same.

Minutes later we were in a backroom Dojo preparing to throw each other onto the hard straw tatami mats. We were not alone. At least ten other officers at the station, including the interpreter, had filed in with us, no doubt, wondering what this young American Marine was all about.

My instructor did not teach me any throwing moves until he was satisfied I knew how to fall. So, for the first twenty minutes, he taught me how to safely absorb the impact of a hard fall to either side and to my back. He taught me how to roll over my right and left shoulders to quickly recover my footing and to end up facing my adversary—techniques not unlike those I had learned in four years of high school wrestling. Nevertheless, he would not show me even the basic throws until I could do the falls to his satisfaction.

That first session lasted about an hour and a half. We would get in only seven more before I had to go back to Korea. Despite the short time we practiced together, he was able to teach me sixteen powerful throwing and submission techniques. The interpreter wrote them down for me in Japanese on a piece of paper that somehow survived Korea and the many other military assignments that followed.

Pencil drawing done by a woman the author met in Sasebo while on his way to Korea in 1953.

Pencil drawing done by a woman the author met in Sasebo while on his way to Korea in 1953.

Thus, my exposure to the ancient martial art of Judo was only a brief one, but what I learned was taught to me by one of the finest instructors in Japan. He was a true master of his art. More than that, he was a good and honorable man who I hold in highest regard, and whose friendship I will always treasure. And yet, I sadly am unable to recall his name after all these years. It wasn’t written on the paper given to me by the interpreter. It is one of the few things I regret.

After one of our practice sessions, he invited me to his home for dinner to meet his family. I was surprised and honored. On the way there, I stopped at a sidewalk food market to buy some fresh fruit and vegetables. He met me there and escorted me to his home; a humble, but nicely arranged living space in a crowded section of Kyoto. I could never have found it on my own amidst the hundreds of other similar dwellings. We took off our shoes and left them outside the door of his home before entering. Waiting for us was his mother, his wife, and a young girl I believe was his sister. I don’t recall meeting his father—the War had taken so many.

After the introductions, I handed the groceries to his mother. She smiled and bowed. I responded in kind. Despite our inability to communicate verbally, I was very much at ease, and they seemed to be, too. It was also my first taste of home-cooked Japanese food and it was delicious.

On the last day of my Judo training, the Chief of Police dropped in and, through his interpreter, invited me to attend the opening of a new sports arena for Judo and Kendo (Japanese fencing). There would be a ceremony honoring the Judo and Kendo Gods, a Samurai sword demonstration, and a Judo and Kendo competition between the police and other teams in Kyoto. The Chief insisted that I sit with him.

Had there been a photographer there to take a picture, he would have seen the Mayor, the Police Chief, several other local VIPs, and a young United States Marine Corporal in a dress green uniform with a single row of ribbons over his left breast pocket. I should have felt out of place among all those distinguished gentlemen, but I didn’t. Perhaps, because I was too young to fully comprehend the singular honor accorded me by my Japanese hosts. It may have also been because the men that sat on either side of me were not in the least uneasy with my presence. Indeed, they made me feel as though I belonged there with them.

The ceremony began with a prayer of homage to the Judo and Kendo Gods and an impressive demonstration of the amazing skills of Samurai swordsmen by two men dressed in black robes. Though they wore no protective armor or headgear, they moved with astonishing speed and precision, wielding their glimmering, razor sharp blades in a blur of motion, missing each other by mere inches.

After an unbelievable display of fencing techniques, one of the men raised his sword high overhead and, with what appeared to be a full-force striking blow, brought it straight down on his partner’s head, stopping it so close you could not see daylight between hair and blade. The picture of that final spectacular move was indelibly etched in my mind.

In the Kendo competition that followed, the competitors wore heavily padded jackets and masks. The sound of their bamboo swords striking their protective armor left no doubt that they were holding nothing back. They fought with equal fervor and skill.

I believed my instructor to be one of the best Judo Masters in Japan. After all, he was Captain of the Kyoto Police Team. On that day, however, I saw just how good he was. In his match, he took his opponent down and forced his submission in less than a minute. His speed and agility were beyond compare, and I was humbled by the realization that a modern-day Samurai had taken time out from his work to teach his art to a young Marine, who, fewer than ten years ago, was his mortal enemy. Only now, writing this story sixty years later, do I truly understand and appreciate the significance of our fateful meeting.

When the matches were over, the contestants respectfully acknowledged each other, then filed out of the competition room and walked upstairs for the celebration banquet. I was surprised to see that the dinner was only for the men. The women, who were dressed in the traditional Japanese Kimono, were there only to serve. They gave each of us a box containing sushi, rice, vegetables, an assortment of other foods, and a set of chopsticks. The box was wrapped in a silk cloth called a furoshiki. They also served warm sake (Japanese rice wine).

Twice now, I have used the word 'serve' to describe the women's role at dinner, but it was so much more than serving. Everything they did—placing the boxes of food on the tables, pouring the wine, and the graceful way in which they seem to glide across the room—seemed to be beautifully choreographed. I felt as though the banquet was more of a ceremony than the one we had just attended. No one touched their food or sake until all were served and the Mayor finished his few words about the occasion. He then ceremoniously unwrapped the furoshiki from his box, which was our cue to start.

I had never used chopsticks before and tried to mimic the man sitting next to me but with little success. He saw me fumbling with the little wooden sticks and showed me how to hold them. I started with the easier items of food and soon gained enough confidence to try the rice. He had obviously been keeping an eye on my progress because, halfway through the dinner, he smiled and said, “You learn very fast.”

I smiled back, and said, “Arigatou gozaimasu.”

After one of our practice sessions, he invited me to his home for dinner to meet his family. I was surprised and honored. On the way there, I stopped at a sidewalk food market to buy some fresh fruit and vegetables. He met me there and escorted me to his home; a humble, but nicely arranged living space in a crowded section of Kyoto. I could never have found it on my own amidst the hundreds of other similar dwellings. We took off our shoes and left them outside the door of his home before entering. Waiting for us was his mother, his wife, and a young girl I believe was his sister. I don’t recall meeting his father—the War had taken so many.

After the introductions, I handed the groceries to his mother. She smiled and bowed. I responded in kind. Despite our inability to communicate verbally, I was very much at ease, and they seemed to be, too. It was also my first taste of home-cooked Japanese food and it was delicious.

On the last day of my Judo training, the Chief of Police dropped in and, through his interpreter, invited me to attend the opening of a new sports arena for Judo and Kendo (Japanese fencing). There would be a ceremony honoring the Judo and Kendo Gods, a Samurai sword demonstration, and a Judo and Kendo competition between the police and other teams in Kyoto. The Chief insisted that I sit with him.

Had there been a photographer there to take a picture, he would have seen the Mayor, the Police Chief, several other local VIPs, and a young United States Marine Corporal in a dress green uniform with a single row of ribbons over his left breast pocket. I should have felt out of place among all those distinguished gentlemen, but I didn’t. Perhaps, because I was too young to fully comprehend the singular honor accorded me by my Japanese hosts. It may have also been because the men that sat on either side of me were not in the least uneasy with my presence. Indeed, they made me feel as though I belonged there with them.

The ceremony began with a prayer of homage to the Judo and Kendo Gods and an impressive demonstration of the amazing skills of Samurai swordsmen by two men dressed in black robes. Though they wore no protective armor or headgear, they moved with astonishing speed and precision, wielding their glimmering, razor sharp blades in a blur of motion, missing each other by mere inches.

After an unbelievable display of fencing techniques, one of the men raised his sword high overhead and, with what appeared to be a full-force striking blow, brought it straight down on his partner’s head, stopping it so close you could not see daylight between hair and blade. The picture of that final spectacular move was indelibly etched in my mind.

In the Kendo competition that followed, the competitors wore heavily padded jackets and masks. The sound of their bamboo swords striking their protective armor left no doubt that they were holding nothing back. They fought with equal fervor and skill.

I believed my instructor to be one of the best Judo Masters in Japan. After all, he was Captain of the Kyoto Police Team. On that day, however, I saw just how good he was. In his match, he took his opponent down and forced his submission in less than a minute. His speed and agility were beyond compare, and I was humbled by the realization that a modern-day Samurai had taken time out from his work to teach his art to a young Marine, who, fewer than ten years ago, was his mortal enemy. Only now, writing this story sixty years later, do I truly understand and appreciate the significance of our fateful meeting.

When the matches were over, the contestants respectfully acknowledged each other, then filed out of the competition room and walked upstairs for the celebration banquet. I was surprised to see that the dinner was only for the men. The women, who were dressed in the traditional Japanese Kimono, were there only to serve. They gave each of us a box containing sushi, rice, vegetables, an assortment of other foods, and a set of chopsticks. The box was wrapped in a silk cloth called a furoshiki. They also served warm sake (Japanese rice wine).

Twice now, I have used the word 'serve' to describe the women's role at dinner, but it was so much more than serving. Everything they did—placing the boxes of food on the tables, pouring the wine, and the graceful way in which they seem to glide across the room—seemed to be beautifully choreographed. I felt as though the banquet was more of a ceremony than the one we had just attended. No one touched their food or sake until all were served and the Mayor finished his few words about the occasion. He then ceremoniously unwrapped the furoshiki from his box, which was our cue to start.

I had never used chopsticks before and tried to mimic the man sitting next to me but with little success. He saw me fumbling with the little wooden sticks and showed me how to hold them. I started with the easier items of food and soon gained enough confidence to try the rice. He had obviously been keeping an eye on my progress because, halfway through the dinner, he smiled and said, “You learn very fast.”

I smiled back, and said, “Arigatou gozaimasu.”

Too young for WWII, Vito Tomasino joined the Marines to serve in Korea. “I don’t want anyone else doing my dying for me,” was the reason he gave his friends. His war over, he then pursued his dream of becoming a fighter pilot, flying two combat tours in Vietnam. When he wasn’t getting shot at he stood watch on bases surrounding the old Soviet Union to ensure that Russia remain behind her “Iron Curtin.” His three books draw from the life of a man who lived during one of the most tumultuous periods in recent history. More on kracek.com.

Use and/or duplication of any content on White Enso is strictly prohibited without express and written permission from the author and/or owner.

Table of Contents Next Page

Proudly powered by Weebly