Being Ruth Asawa

By Anne Whitehouse

“We do not always create ‘works of art,’ but rather experiments;

it is not our ambition to fill museums: we are gathering experience.”

— Josef Albers

it is not our ambition to fill museums: we are gathering experience.”

— Josef Albers

|

“When I’m working on a problem, I never think about Beauty, I think only how to solve the problem.

But when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.” — R. Buckminster Fuller |

|

I remember sitting in the back of my father’s horse-drawn leveler, dragging my big toe in the dirt path between fields, making looping, hourglass designs. This was in the 1930s, outside Los Angeles, California. My father leased land he couldn’t own because of the law against foreigners. My mother was a Japanese picture bride, betrothed on the promise of a photograph. I was fourth of their seven children. Our father built our house of board-and-batten, with a paper ceiling and a tin roof. He knew how to use water wisely and grew beautiful vegetables from that earth. |

We toiled alongside our parents,

planting, weeding, harvesting,

nurturing the soil.

But our father was cheated at market.

We were so poor we salvaged

nails from shipping crates.

We trapped gophers for meat.

planting, weeding, harvesting,

nurturing the soil.

But our father was cheated at market.

We were so poor we salvaged

nails from shipping crates.

We trapped gophers for meat.

|

Through persistence and perseverance,

our father increased his leasehold to eighty acres. He hired laborers. We owned two cars and two tractors. He was a father to his brother’s five children as well as to us, after his brother died. |

|

After Pearl Harbor was bombed,

he made a big hole in the ground where he buried our Kendo swords and gear. He burned the beautiful Japanese books on the tea ceremony and flower design and the precious dolls and badminton paddles my sister had brought from Japan just months before. One Sunday in February 1942, two men in dark suits surprised us as we worked in the fields. They took our father by the arm and marched him to the house. They watched him eat lunch. He finished his meal with a slice of my sister’s lemon meringue pie, and then they drove him away. |

I learned later they were FBI

and suspected our father

of being a traitor.

He disappeared from our lives.

Four years passed before

we saw him again.

and suspected our father

of being a traitor.

He disappeared from our lives.

Four years passed before

we saw him again.

|

Soon, with thousands of others,

we were assigned to a detention camp in Santa Anita. We lost almost everything we owned. We lived in the stables of a converted racetrack surrounded by barbed wire. Hair from the horses’ manes and tails stuck between cracks in the walls. In the summer heat, the smell of horses was overpowering. The excuse for separating us from our homes and livelihoods was that the U.S. was at war with Japan where our parents were from. Yet there was no similar removal of Italian or German Americans. In the camp, I noticed three men who liked to sit together high in the grandstand of the racetrack, balancing sketchpads on their knees, drawing pictures with pieces of charcoal. They didn’t seem to mind the dust that blew up from the track, or the sun, or if I sat with them. They encouraged me. That was how I learned I was an artist, too. They were my teachers-- Tom Okamoto, Chris Ishii, James Tanaka-- Disney artists who’d drawn Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, Donald Duck, and Mickey Mouse--now suspected of being “enemies of the people.” Yet I saw how when they worked, worry fled. In the midst of hardship, their concentration made a peaceful space where something unexpected and beautiful might happen. Wire selected me, not the other way around. We had it on the farm, and even as a child I noticed how useful it is and how transparent a barrier. Wire starts out as a line, a boundary between two places, inside and outside, left and right, But wire can also be transformed into a three-dimensional object. In the summer of 1947, when I was an art student at Black Mountain College, I joined a public service project to teach art to children in Toluca, Mexico. In the market I noticed the wire baskets made by farmers to carry eggs and produce. They needed no tools but their own hands. They taught me how to wrap wire in even loops around a dowel. Interlocking loops formed rows which could be varied by size and shape by adding loops or subtracting them. It was like crocheting without a hook or knitting without needles. |

|

When I returned to Black Mountain,

my first sculptures were baskets like the ones the Mexican farmers made. When I joined the beginning to the end, they became rounded, like fruits. Next they stood up and took flight. They asked me to consider, what is inside, and what is outside? I have spent my life finding out, layering form within form, voluptuous, swelling. Was I thinking of motherhood, of my own children? Yes, and no. Making art is a different mental process. Any artist will understand. My great teacher, Josef Albers taught the use of negative space, beauty in repetition, and the cultivation of a deep awareness. He wasn’t interested in feelings. If you want to express yourself, do it on your own time, he said, not in my class. Some of the students resented this, but I come from a culture where personal feelings are hidden. Albers said, Draw what you see, not what you know. Even black will change. Never see anything in isolation. Define an object by defining the space around it. I understood this, too. As a child, I studied calligraphy where we learned to consider the spaces between the brushstrokes as well as the brushstrokes themselves. Albers also said, Art doesn't know progress or graduation. Year after year he taught the same courses-- design, color, drawing and painting, presenting us with the same problems, concepts, and assignments, but each time was never the same. |

|

I learned that nothing is ever settled

in life or in art. Sometimes adversity yields an advantage. It’s like looking for a light in darkness. Your eyes will sometimes betray you, but eventually you’ll find a way out. Our detention in Santa Anita was temporary. After five months, we were sent to the Rohwer Relocation Center in the swampland of southeast Arkansas, where eight thousand Japanese immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent lived in communal barracks. We shared lavatories, a laundry, a kitchen, and dining hall. The soil between the barracks turned to black muck when it rained. Cypress trees grow in the bayous, and creeks snaked through fields worked by sharecroppers. |

|

The eerie beauty of that landscape,

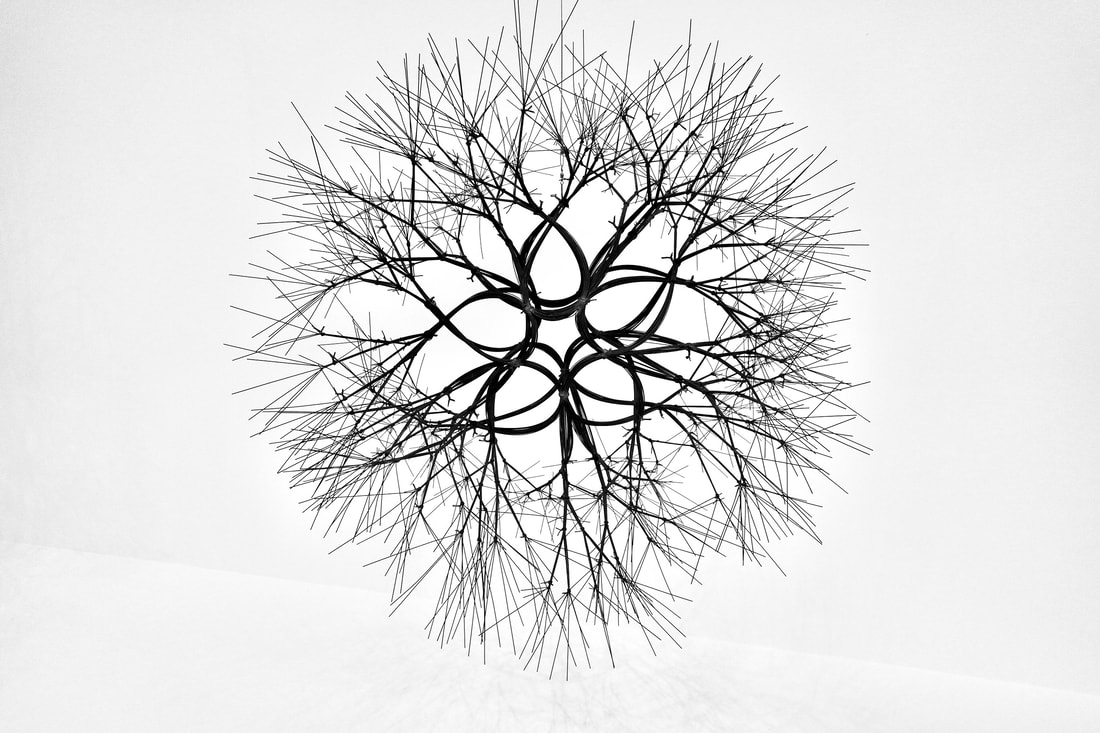

half earth and half water, has stayed with me, the gnarled cypress knees that grew straight up from their hidden roots through dark water. We searched the swamps for the most unusual shapes. Sanded and hand-polished, they became doorstops, useful and ornamental. My mother had brought seeds, and we planted a garden. We kept chickens and a pig. At Rohwer, we went to school. Every morning we pledged allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. When we came to the end, “with liberty and justice for all,” we added under our breath, “except for us.” Living with my family on the farm, I had been an obedient Japanese girl. At Rohwer, I learned to question authority. Imprisoned as un-American, I became American. Living the way we did, without our father, our family ties loosened. Students at Rohwer were allowed to attend college, if the college was in the middle of the country. The Quakers provided assistance. In 1943, my sister Lois left for Iowa. Chiyo followed her. I was next. I picked the Milwaukee State Teachers College, because it was the cheapest in the catalog. I boarded with a family as a live-in maid. Three years passed-- my father was released, the war ended, but I was told I couldn’t graduate. Because of my Japanese background, no one would hire me as a teacher. Before I left Rohwer for college, our teacher, Mrs. Beasley, told us not to harbor any bitterness from what had been done to us. It was wrong, but to dwell on it would only hurt us and hold us back. All I had strived for was destroyed when I wasn’t allowed to graduate. But what seemed the collapse of my hopes was the prelude to my transformation. There were two doors, and I opened both. They seemed to lead down separate paths but, in fact, they intersected. In the summer of 1945, my Milwaukee friends Elaine and Ray wanted me to come with them to Black Mountain College in North Carolina, but I went to Mexico City with my sister Lois instead. I studied design with Clara Porset, a Cuban artist at the University of Mexico. Clara had also been to Black Mountain. The next summer, I went there, too. Some educational experiments are destined to flower and fade. Black Mountain College had a brief lifespan. I was one of the lucky ones. College life was like detention camp turned inside out. The college was also land-rich and dirt poor. We were encouraged to find ways to do what we wanted with the few resources we had. Teachers and students ate together, and everyone had to work. I gave haircuts to students and teachers, worked in the school laundry, and woke in the early morning to churn butter and make cheese. How the Europeans loved soft butter and buttermilk at breakfast! Many of the teachers were refugees. Their culture made the college what it was. Without the war, it would not have happened. For a brief time, while it existed, it was a haven for those who had suffered because of their race, religion, or skin color. My parents’ Buddhism consisted of rituals they never explained. At Black Mountain College, we learned the precepts of Buddhism. My studies gave me insight into the religion of my ancestors. There was harmony and affinity between the principles of my college and the values of my heritage. Rising before dawn to make butter for breakfast, I would knock on Albers’ door to wake him on my way to the barn so he could photograph the fog lying low over the mountains. He would snap a few pictures and go back to sleep. When the cold fog from San Francisco Bay comes rolling in through the big windows of the high-ceilinged living room of our brown shingled house on Castro Street, I sometimes remember the early morning mountain fog in North Carolina. At Black Mountain College, I explored the land around me as I had not done since childhood, observing the trees and bushes, vines and wildflowers. One day, after I’d been there a year, I was walking on a forest path when I felt someone’s eyes on me. I turned and found myself looking directly into his gaze. It was Albert Lanier. He had been watching me before I noticed him. Our backgrounds and upbringing couldn’t have been more different, yet we never had any doubts about our love for each other. We knew what we would be facing as an interracial couple raising a family, but Albert was an architect and builder and used to finding a way, and I knew how to work hard. We weren’t likely to give up. On a rainy summer day in 1948, Albert and I watched from a ridge with the rest of the college, while our teacher, Buckminster Fuller, connected the designated points of a dome he had designed out of strips of Venetian blinds. When it failed to rise, he didn’t give up. The next summer he returned with different solutions, and this time, the dome stayed up. There is no success without failure; you succeed when you stop failing. At Black Mountain College, Albert built a Minimum House with cheap industrial materials and what was at hand. He diverted a creek to flow around the house. The house took a year to complete. There was a large room for living and sleeping, a kitchen, a bath, and closets. Albert constructed a terrace of flat fieldstone and two walls of brown fieldstone striped with lichen that he collected in the woods. I advised him how to place the stones to make a pattern, side by side and up and down. When Minimum House was finished, Albert left to learn the building trades in San Francisco, where it was legal for us to marry. I planned to join him in a year. Bucky Fuller designed our wedding ring as his gift to us-- a black Lake Huron stone in a setting formed by three “As” for “Asawa.” I felt I needed to warn Albert what it meant to marry me: My parents dare to be tolerant because we have all suffered intolerance. I no longer want to nurse such wounds. I now want to wrap fingers cut by aluminum shavings, and hands scratched by wire. Only these things produce tolerable pains. You will have to look at me on the streetcar or bus when you hear someone shout, ‘dirty Jap.’ I hope we never have to experience it, but expect it, do not fear it. I’ve overcome most of the fear. This attitude has made me a citizen of the universe, by which I grow infinitely smaller than if I belonged to a family, province, or race. I can allow myself not to be hurt by ugly remarks, because I no longer identify as a Japanese or American. Our wedding took place two days after my arrival, on July 3, 1949, in a loft over the onion warehouse that would be our first home. I knew I wanted a large family. Josef and Anni Albers, who were childless by choice, were skeptical. Before Albert left Black Mountain, Albers took him aside and said, “Don’t ever let Ruth stop working.” Albert’s work made mine possible. We had six children in nine years: Xavier, Aiko, Hudson, Adam, Addie, and Paul. Raising children, growing a garden, and making art were all connected for me. I created my sculptures with my children around me. I wanted them to understand that art does not have to be separate from the rest of life. It can be as ordinary and essential as breathing. Bucky worked by trial and error, Albers was interested in ideas that didn’t have a shape yet. My ideas come from nature. I start with general principles that apply to anything I do. Instead of forcing a design onto my material, I try to become background, like a supportive parent who enables the child to express itself. Each material has a quality of its own. By combining it or putting it next to another material, I change it or give it another personality, without destroying either one. When I separate them again, they return to what they are. It’s the same with people. You don’t change someone’s personality, but combined with other people, a person will take on different features. The intent is not to alter, but to bring out another aspect. A line can enclose space, while letting air remain air. My wire sculptures are a continuous surface. I begin from the inside, and as it takes shape, it comes out and in again while remaining, essentially, itself. What interests me are the proportions. I folded origami as a child, but my folded sculptures come from my work with Albers. We folded paper in the European way, which is structural. We learned about the strength of certain angles. You can fold a sheet of paper so you can stand on it, as if it were made of wood. With paper, you can easily change the folded angle, but metal is rigid. You fold metal just once. My friends Paul and Virginia brought a desiccated plant from Death Valley for me to draw. The gnarled trunk branched off symmetrically, ending in feathery fronds. To understand its structure, I modeled it in wire, which led to my tied metal sculptures. I start with as many as a thousand strands of wire in a single bundle. Using a pair of pliers to cut and twist the wires, I divide the bundle into thirds. I continue to divide each branch until only two strands are left. I tie each joint with the same wire. No solder is used. When I create the tied center, I have already made a decision. It interests me to work out variations of the same idea, instead of following different ideas. My sculptures are meant to be suspended from the ceiling, mounted on a wall, or on a base. Bronze wire stays green a long time. Brass wire turns dark. Immersing it in an electrically charged sulfuric bath leaves a greenish cast. The ends, dipped in resin, resemble raindrops. I asked the plating company to run the electric current backwards, creating a rough surface. One quiet Sunday morning, scavenging for materials on a San Francisco street, I found coils of enameled copper wire on a sidewalk outside a bar. They came from the insides of smashed-up slot machines that the city had recently outlawed and ranged in color from rust-red to purple and blue-back. To be alert to my surroundings is to be aware of opportunity. When I was a child on the farm, I shaped wire into rings and bracelets. At Black Mountain we were encouraged to use what we could find and was at hand. When I worked in the college laundry, I made drawings using the BMC stamp. Albers’ concept of the meander influenced my studies of sequences, patterns and contrasts, curves and reversals, and optical illusions that “swindle the eye.” As the last rays of sunlight cast shadows across my living room, I sit cross-legged on the floor, with the wire in my lap and my hands on the wire, my children around me, reading or doing their homework, playing or practicing the piano. Above us, my wire sculptures tremble and sway, in a dance with the air. I feel they are protecting us, like household gods. I am often asked how I can bear the tedium of my artistic process. Farm work is by nature tedious and repetitive, and I grew up on a farm, planting a thousand seeds at a time, pulling hundreds of weeds, harvesting fruit and vegetables by the bushel. As I work, I fall into a rhythm, and the tedium becomes absorbing. At Rohwer, I was proud of how well I strung my beans on the trellis I made, working from the bottom to the middle to the top. I often construct my sculptures in the same way. My process is about the cultivation of patience and stillness, of learning to be nonreactive and sit with discomfort, and it has made me a better wife, daughter, mother, teacher, and friend. I tell women who want to make art, Don’t wait until it’s too late, and you don’t have the energy. You don’t need long stretches of time. Learn how to use your small snatches of time as they are given to you, and they will add up. After the war, my parents never got back the leases they lost. They started over working for someone else in Arizona. They were simple people. They wanted me to be lucky, not in money or honors, but in life. When I work, I am at one with the spirit of my material. Don’t be afraid of the unknown. The unknown is what will free you. |

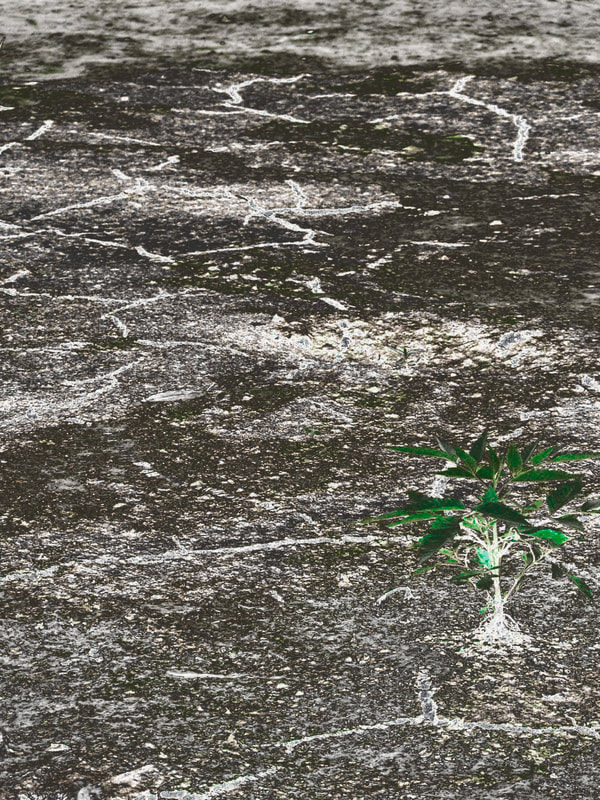

Header photograph by Anne Whitehouse.

Anne Whitehouse’s poetry collections include THE SURVEYOR’S HAND, BLESSINGS AND CURSES, THE REFRAIN, METEOR SHOWER, and OUTSIDE FROM THE INSIDE, the last three from Dos Madres Press. She is the author of a novel, FALL LOVE. She has published essays and lectured on Longfellow and Poe. Her chapbook, FRIDA, about Frida Kahlo, is forthcoming from Ethel Zine and Micro Press. She is from Birmingham, Alabama, and lives in New York City and Columbia County, New York.

@anne_whitehouse

Anne Whitehouse’s poetry collections include THE SURVEYOR’S HAND, BLESSINGS AND CURSES, THE REFRAIN, METEOR SHOWER, and OUTSIDE FROM THE INSIDE, the last three from Dos Madres Press. She is the author of a novel, FALL LOVE. She has published essays and lectured on Longfellow and Poe. Her chapbook, FRIDA, about Frida Kahlo, is forthcoming from Ethel Zine and Micro Press. She is from Birmingham, Alabama, and lives in New York City and Columbia County, New York.

@anne_whitehouse

Use and/or duplication of any content on White Enso is strictly prohibited without express and written permission from the author and/or owner.

Table of Contents Next Page

Table of Contents Next Page

Proudly powered by Weebly