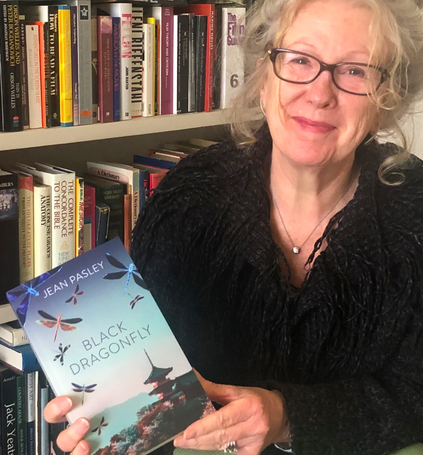

Black Dragonfly

by Jean Pasley

Reviewed by Ronan O'Driscoll

Click here to read an excerpt from Black Dragonfly.

I was gutted when Jean Pasley’s novel about Lafcadio Hearn’s life in nineteenth-century Japan was released. Oh no, I despaired, I wanted to write this!

I had often felt that Hearn was under-appreciated, particularly in his native Ireland. After an early life of wandering in Cincinnati, New Orleans, and Martinique, Hearn settled in Japan. His writings on Japan’s culture and folklore introduced the newly opened country to the western world and are still respected today. However, in 1990s University College Dublin, when I studied Hearn’s contemporaries Wilde and Yeats and their fascination with the Orient, there was no mention of Hearn.

Jean Pasley’s novel addresses that lacuna. She sets the scene of a young Lafcadio Hearn arriving as a teacher to a suddenly modernizing Japan, still dramatically different from the West. I had visited Japan through the JET program, so instantly identified with the young Hearn, who sought the “true” Japan and awkwardly made culturally inappropriate gaffes along the way. I cringed when I read about Hearn demanding of his Japanese friend Akira to drop his family duties during Obon, one of Japan’s two most important and cherished festivals, for his story recalled similar mistakes of my own. Like Hearn, I was the first Westerner to live in my town, a mountain community about three hours outside of Kobe. Reading Pasley’s novel, I am struck that the Japanese mountain town of my time—pre-internet and no flush toilets—was as different from today’s Japan as it was to Hearn’s in nearby Matsue.

Pasley does an excellent job of creating a fictional account of Hearn’s world using facts and excerpts from his notes, letters, and books to show the many faces of the man, from his petulant and self-indulgent sides to his growing empathy and understanding for Japan. The story also highlights Hearn’s joy at stepping into the role as head of his much younger wife Setsuko’s down-on-its-luck samurai family, but also describes his yearning to abandon them and return to his beloved Martinique.

Setsuko is also a revelation under Pasley’s hand. Like Catherine Ronayne—Hearn’s Irish nanny who instilled in him a love of ghost stories—Setsuko knows how to calm down the sometimes overwrought Lafcadio with a fable or two. Indeed, Black Dragonfly brings Setsuko to the fore as the source of many of the ghost stories Lafcadio recorded. Hearn’s love for Setsuko and Japan matured and transformed him from the unsettled man he was in his earlier life.

Pasley titled her novel Black Dragonfly because Hearn was fascinated with a dragonfly in his garden. He is told that dragonflies are creatures that transform from birth in the element of water to the entirely different element of air when they mature. The novel is an account of how the element of Japanese culture and his relationship with Setsuko changed Hearn utterly. Especially, it made him blossom as a writer to record the ghost stories for which he is most remembered today.

Jean Pasley’s novel is a nuanced and evocative retelling of a complicated life. Reading the story brought back so many personal details of my own time there, without any of the clichés often associated with this kind of tale. The research that went into the story is worn lightly, never overburdening the narrative. Indeed, the layering of the facts with the fictional narrative gives the reader a feeling of being transported to the Japan of Hearn’s time. It isn’t every day you finish a book and think: I not only wanted to write this story, I would have written it exactly that way.

|

Book details

Black Dragonfly by Jean Pasley Balestier Press Available in Japan at Kinokuniya Books and internationally on Amazon. |

Side Note from Ronan O'Driscoll:

Hearn's Irish nanny, Catherine Ronayne, is attributed to instilling Hearn with a love for ghost stories. My mother’s maiden name of Ronayne (the reason I am called Ronan) is a rare surname in Ireland, so it is not too much of a stretch to find a familial connection. (No connection to 浪人--ronin, or masterless samurai—though!) Like Hearn, moving to Japan as a young man was a means of finding myself, and like Hearn, I fell in love and married there—not to a Japanese woman but to a Canadian. We live in Nova Scotia now, with our three children. But that’s another story. |

Ronan O’Driscoll is the author of Poor Farm, published by Moose House Press, and Chief O’Neill, published by Somerville Press. Poor Farm is an imagining of what might happen to an autistic young man in nineteenth century Nova Scotia. Chief O’Neill covers the life of Francis O’Neill (1848-1936), another wandering Irishman who ended up in America as Chicago chief of police, remembered today for his collections of Irish tunes. He lives in Nova Scotia with his wife and three children. For more details visit https://ronanodriscoll.com.

Use and/or duplication of any content on White Enso is strictly prohibited without express and written permission from the author and/or owner.