Seeking Sakuichi

by Shizue Seigel

When I left for Japan in 2003, my mother handed me a 3x5 card with the names of my long-dead grandparents written out in English and kanji— Sakuichi Tsutsumi and Umematsu Yokote—and the names of their villages written in romaji English—Itakusu and Kita-Itakusu, Kumamoto, Japan. I read the words out loud, rolling the syllables over my tongue. Such slender threads to my family’s past in Japan.

“What about addresses, Mom? Baachan used to be so happy to get letters from Japan.”

She shrugged. “Mama died twenty years ago. Nobody kept those letters. We couldn’t really read them.”

I pushed a map of Japan towards her with an edge of desperation in my voice, “Do you recognize any names?”

She scanned the map. The smaller villages were written only in kanji that neither of us could read. Finally, Mom spotted a larger town labeled in both English and Japanese. She cried out, “Yamaga! Mama used to say it was the nearest big town.”

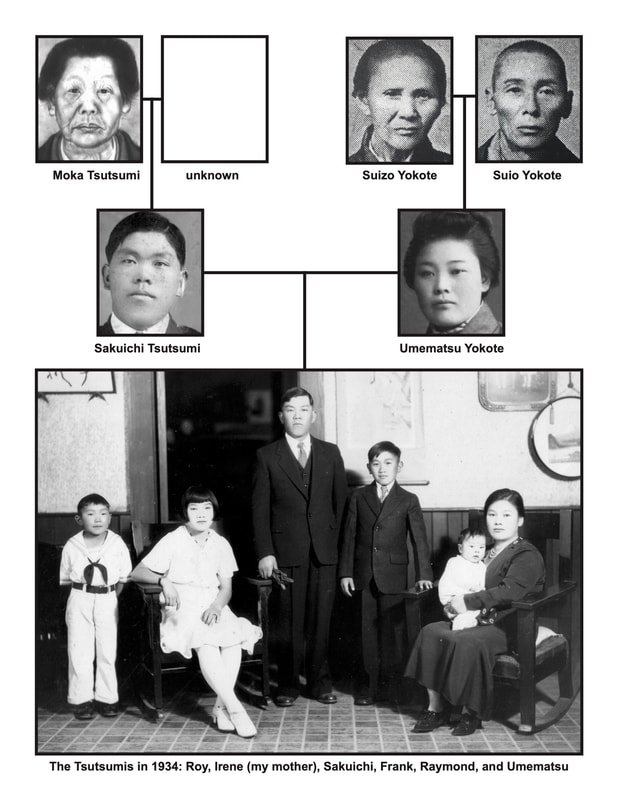

This was my first trip to Japan since I was 11, and I was determined to find out more about my grandfather, Sakuichi, who had established our family in America. He’d died in 1934 when Mom was 13, but his memory loomed large. Our photo albums were stuffed with pictures of an earnest, broad-faced man whose warm strength of character outshone his low brow and crooked teeth. Sturdy goodwill beamed from a photo of him in kimono before he immigrated to California in 1905. In a photo from 1912, he wore a fine suit and tie, watchchain stretched across his vest. He'd courted my grandmother Umematsu, a girl from a neighboring village, with that portrait of himself as a successful businessman, along with more photos of him and his partners working their first fifty-acre farm.

Sakuichi’s first seven years in California had earned him enough to send for his bride and to dress her in an ostrich plume hat and a shirtwaist with mutton-leg sleeves. More photos of growing good fortune were punctuated by their only trip back to Japan in 1928 to inter the ashes of their first two children.

Western-style clothes traced the passage of time and status, from work shirts to three-piece suits, from sunbonnets to a fox-fur stole, but ties to the old country pervaded my grandparents’ daily lives in California. They spoke Japanese, ate Japanese-style meals, grew vegetables as they had in Japan, shopped in Japantown, and prayed at the Buddhist temple that they and their fellow immigrants helped build. Whenever times got tough in America—and they did—my grandmother stood on a cliff at the edge of the Pacific and gazed homeward. The emotional pull was so strong that I wondered why they’d never returned.

I was born and raised in the United States, as were my parents. I grew up mainly in all-white neighborhoods, but long stays with my grandmother anchored my identity as a Japanese American. They were the stable warp that steadied the uneven, up-and-down weft of life in America.

My baachans and uncles and aunties passed on a love of nature and a pull towards kindness and gratitude. My heart was lifted by wabi-sabi and chambara movies and illuminated by the simple sight of a ginko leaf and plum branch, soothed by camellia pink and tea green. My father liked to claim samurai lineage, but my blood is alive with dirt farmers, housemaids, and gardeners that felt no need to be anything but their plain-spoken selves.

In 2003, I was going to Japan with a decent Japanese accent, but a three-year-old’s vocabulary. I was nervous about trying to navigate my way to a tiny village on the backside of Japan’s southern island. I’d been shocked and hurt during a layover in 1972 in transit from India to San Francisco. Tokyoites scorned my halting pleas for help with the jumble of subway ideograms. They looked at my Japanese face and assumed that I was a native speaker pretending to be like my gaijin—foreign—companion.

.

Thankfully, thirty years later, I found that Japanese nationals understood that people who looked like them could have been born in other countries. “Amerika-jin dakara, amari wakarimasen (I’m American, so I don’t understand much),” drew quick and sympathetic understanding in tourist-savvy Kyoto, where it was a snap to book fast trains and reserve rooms through English-speaking agents.

So I felt confident as Ben and I stepped off the shinkansen at the Kumamoto train station. We headed straight for the tourist information booth.

“Sumimasen, Itakusu wa doko desu-ka (Excuse me, where is Itakusu village)?” The young clerk was friendly, but her English was worse than my Japanese. She riffled through a phone-book-sized directory and shook her head regretfully. “Sore wa sonzaishinai (It does not exist).”

“Mata mite kudasai. Yamaga ni chikaku (Can you look again? It’s near Yamaga.),” She looked through the directory again. “So-re wa son-zai-shinai,” she enunciated slowly.

How is that possible? I wondered. How could a whole village cease to exist? I visualized houses tumbling into a sinkhole. The clerk conferred with a supervisor who delivered a long Japanese explanation and summed it up in English.

“New system. We cannot help. Record office. Monday.” They both bowed regretfully.

So close, yet so far! Sakuichi’s village had disappeared. Our journey was over before it started. Dejected, we dropped our luggage at the hotel, then strolled through the town, passing an ungainly jumble of concrete offices and residences. A sign with the kanji for “river” led us to the barren footpaths of a river lined with riprap. To my disappointed eyes, the city was a nondescript sprawl with none of the antique and precious charm of Kyoto.

In search of food, we entered a covered arcade crammed with brightly-lit shops hawking jeans and children’s wear and blasting Western music. Fashionably dressed young women bought toilet-seat covers and shower curtains at a giant Hello Kitty store. We ate at a chain restaurant filled with office workers slurping mediocre ramen with their backs turned to each other. So much for conversation and local color.

As we trudged back to our hotel, my travel companion Ben noticed a sign that read ‘John’s Bar.’

“Let’s check it out. The guidebook says it’s owned by a gaijin,” he said. We descended narrow cast-iron stairs to a closed basement door. When we pushed it open, a foreigner’s voice rang out crisply from the dimly lit interior. “Closed tonight. Sorry.”

“We weren’t looking for a drink anyway,” I said, smiling apologetically at a middle-aged man with a neatly trimmed beard and a New Zealand accent. “We just wanted to talk to a foreigner about what it’s like to live in Kumamoto City. Do you have a few minutes to spare?”

He beckoned us in with a cock of his head. He loved Kumamoto City, he said. He’d arrived ten years earlier to study kendo in the home city of fabled swordsman Miyamoto Musashi. Kumamoto was still a world-class center for martial arts, and many champions were members of the city police force. John had married a Japanese woman and become a high school English teacher. The bar was something of a hobby, a gathering place for expatriates, and a venue for his amateur rock band. As a matter of fact, they were rehearsing that night.

Band members trickled in. While they hooked up their amplifiers and speakers, Ben and I talked with Eddy, the vocalist. He was a Japanese civil lawyer who had honed his excellent English during a two-year stint in Toronto. He was intrigued when I explained that we had come to search for my grandparents’ roots.

“What is the name of the village?”

“Itakusu,” I said, “but it seems to have disappeared.”

“Oh, it’s still there,” Eddy said. “Several years ago, the government consolidated small villages into larger townships. Itakusu and Kita-Itakusu are now part of Mikawa town. My wife comes from near there. It’s about an hour-and-a-half away by bus.”

I could hardly believe that chance had led us to a dark, basement dive and a stranger who could set us on the right path. Eddy kept detailed village maps in his car for his work.

“Hey guys,” he called out to his colleagues, “can you practice your instrumentals while I help these folks?” Eddy and Ben went to make color copies of his maps while I marveled that the mall had a copy store open at 8 pm on a Friday. When they returned, Eddy spread out the maps on a table and traced out the route to Itakusu. He even knew the route number of the bus to Yamaga, the nearest large town.

“You’ll have to transfer there. I don’t know the bus number to Itakasu, but someone should be able to help you. And go tomorrow; the smaller routes don’t run on Sundays.”

Thank goodness Eddy had given us the Yamaga bus number. At the terminal, we couldn’t understand the kanji, only the route numbers. When we reached Yamaga, housewives at the bus stop clustered around Eddie’s map and steered us onto the bus to Itakusu. They were intrigued that I was a Sansei whose ojiisan had gone to America ninety years before. They clucked over us like protective hens. Before they got off the bus, they passed my story along to newly boarding passengers who agreed to make sure we didn’t miss our stop.

A woman who got off at the same stop we did pointed to a sprawling concrete-slab building across the street and nodded encouragingly. Ben and I paused to take in our surroundings. There seemed to be no town to speak of. Aside from what looked like a light industrial building and a grocery store, we were in the country. No lodgings or eateries in sight. A wide creek meandered through drab winter fields punctuated by thin scatterings of houses. The woman pointed again towards the big building and shooed us firmly across the road.

There was a sign outside, but of course, we couldn’t read it. It didn’t look like my idea of a government building at all. Hesitantly, we walked inside. At the counter. I explained in English that I was looking for my grandparents’ koseki (family registries). I produced my mother’s 3x5 card and pointed to my grandparents’ names. He asked for my passport and birth certificate and showed them to his supervisor, then tapped into his computer. In about two minutes, the printer spit out two documents printed on blue-flowered paper. “Ojiisan,” the clerk articulated slowly, pointing to the right sheet. He tapped out ¥1500 on his calculator, and then waved to the other paper. “Obaasan.” Another tap on his calculator, another ¥1500. He showed us the total and bowed.

For ¥3000, about 30 bucks, I had the treasure I’d been hunting: my grandparents’ registries. And I couldn’t read a word.

I would have to wait until I returned home for my Uncle Frank’s Japanese wife to translate the scratchy black writing that filled the form’s many boxes. Stunned by how quick and easy it had been to get the koseki, I tottered out of the building, bowing and thanking the clerks who waved as they peeped out from their cubicles.

We still had no clue where my grandparents had actually lived, but I was walking where they once might have walked!

The afternoon was winding down. We knew buses ran every two hours but had no idea when they might shut down for the night. We didn’t have time for serious exploring, so we walked along the creek to absorb as much of the landscape as we could—fallow fields, dry and brown in winter; steep hills thickly forested with bamboo; the shallow, gravel-bedded creek. Most of the houses looked new, with black tile roofs and plaster walls. They were a little bigger than they’d probably been in 1910. The landscape seemed to have changed little, and I thought, if my grandparents had come back again, they probably would have recognized their neighbors’ fields and homesites. It was so heart-achingly beautiful that I could not help but wonder why my grandparents hadn’t returned.

If Itakusu had changed so little, California had changed dramatically during the same period. The fruit orchards and vegetable fields that transformed the Santa Clara Valley in the “Valley of Heart’s Delight” in the early 20th century had been plowed under, never to return. Fertile soil was now covered by asphalt and concrete, transformed into the office parks and glossy suburbs of Silicon Valley.

We had not walked very far when a small car beeped and roared to a stop in front of us. Were we trespassing, I wondered? No. The town clerk leaped out of the car with a smile and explained in a mixture of English and Japanese that my grandfather’s koseki was incomplete. He exchanged the earlier one for a more accurate version.

Before heading back to work he asked, “Doko ni iku no (Where are you going)?” I shrugged. “Just for a walk.” He nodded and pointed farther upstream. “Kita-Itakusu.”

We walked about a half-mile, past more fields and small clusters of houses. My great-grandmother was from here. Our luck had been good so far; would it bring me even closer to my family?

Before I left, my mom had remembered the name Moka Tsutsumi, Sakuichi’s mother and my great-grandmother. She died in 1948. Would we be able to find out something about her?

I asked an elderly woman we encountered. “Moka Tsutsumi oboetemasu-ka? Go ju go-nen mae shinda (Do you remember Moka Tsutsumi? She died in 1948.).” She shook her head and backed away. Was it from my bad Japanese? Maybe, but it didn't deter me. I asked a balding old man in rubber boots hoeing his field.

“Ah, so desu-ne,” he nodded, “asoko ni sunde imashita.” He pointed back towards a cluster of houses we’d passed. My great-grandmother had lived there, he said.

We were on our way to that area when the old man roared up on a motor scooter. He explained excitedly that the man who had taken care of my great-grandmother had just driven by in his pickup and would wait for us in his front yard. The old man waved away our thanks and scootered back to his field.

Shogo Tsutsumi was indeed waiting outside his house, a tall, serious man with a thick shock of hair. He invited us inside, apologizing for not remembering a word from the English classes he’d taken. As his wife served tea and senbei, he pointed to the large, elaborate butsudan in a corner alcove. Photos of his parents and Moka held a place of honor on the Buddhist shrine. Centered above the living room doorway was an oil painting of Moka in formal black kimono with crests on the sleeves.

Despite the common surname, Shogo explained, he and Moka were very distant cousins, not closely related. But his father and my grandfather had been dear friends and neighbors. Shogo’s father had agreed to care for Moka in exchange for the family’s small parcel of land. He explained that Sakuichi and Umematsu sent money when they could, and when Moka grew too old to live alone in her own house, Shogo enlarged his house so she could live with them.

He rummaged in a closet and brought out some ancient photos of Moka and my grandfather. He seemed embarrassed that the images were curled and mildewed. I recognized almost all of them. Our family had copies in America. Like most Issei immigrants, my grandparents sent portraits home regularly, and they preserved the photos they had received in return, solemn portraits of kimono-clad strangers whose names and relationships had died with my grandparents.

We had not finished our tea when Shogo’s wife appeared with another tray, laden with coffee and sliced fruit. I hadn’t expected to meet anyone in Itakusu who remembered my family, so hadn’t brought omiyage (visiting gift). I tried to apologize for my rudeness, but Shogo and his wife looked at us blankly. We’d exhausted our shared vocabulary, so we sat on the tatami and grinned at each other awkwardly.

It was nearing dinnertime and we had to catch the bus. As we made our farewells in the yard, Shogo asked if we planned to visit Moka’s grave. He pointed to the Buddhist temple on the far side of town. No, I told him. It was getting late, and we were afraid we’d miss the last bus. It occurred to me that I was committing another serious breach of etiquette by not visiting the gravesite, but the Japanese phrase “shouganai” came to mind. There was nothing that could be done about it.

As we left, I heard Mrs. Tsutsumi say to her husband, “They didn’t take the photos.” I groaned inwardly. I thought they were simply showing us the photos, not gifting them. I pretended I hadn’t heard, thinking it was best to leave before I committed any more stupidities.

As Ben and I walked back to the bus stop in the gathering dusk. I felt embraced by the kindnesses offered again and again by the many strangers who’d helped me find my grandfather’s home. With a full heart, I soaked in the forested hills, the thatched houses, the river meandering through the fields—it was the very picture of the furusato village, the old home that Issei immigrants longed for.

As the bus wound its way from one mountain valley to another, I tried to envision my grandfather’s journey along this route. When the hills opened out to the broad plains, high mountains, and prosperous farms around Yamaga, I realized what drew him to California. The wide, rich valley around Yamaga resembled San Luis Obispo, where my grandfather established his first farm. He must have thought he’d died and gone to heaven when he went from a tiny plot in Japan to a share in a 50-acre farm within five years of arriving in California. By the time he died from an auto accident in 1934, he was one of the county’s largest growers, raising peas, beans, broccoli, lettuce, and cabbage on 140 leased acres. He did not live to see my grandmother lose it all when the family was incarcerated after Pearl Harbor.

“What about addresses, Mom? Baachan used to be so happy to get letters from Japan.”

She shrugged. “Mama died twenty years ago. Nobody kept those letters. We couldn’t really read them.”

I pushed a map of Japan towards her with an edge of desperation in my voice, “Do you recognize any names?”

She scanned the map. The smaller villages were written only in kanji that neither of us could read. Finally, Mom spotted a larger town labeled in both English and Japanese. She cried out, “Yamaga! Mama used to say it was the nearest big town.”

This was my first trip to Japan since I was 11, and I was determined to find out more about my grandfather, Sakuichi, who had established our family in America. He’d died in 1934 when Mom was 13, but his memory loomed large. Our photo albums were stuffed with pictures of an earnest, broad-faced man whose warm strength of character outshone his low brow and crooked teeth. Sturdy goodwill beamed from a photo of him in kimono before he immigrated to California in 1905. In a photo from 1912, he wore a fine suit and tie, watchchain stretched across his vest. He'd courted my grandmother Umematsu, a girl from a neighboring village, with that portrait of himself as a successful businessman, along with more photos of him and his partners working their first fifty-acre farm.

Sakuichi’s first seven years in California had earned him enough to send for his bride and to dress her in an ostrich plume hat and a shirtwaist with mutton-leg sleeves. More photos of growing good fortune were punctuated by their only trip back to Japan in 1928 to inter the ashes of their first two children.

Western-style clothes traced the passage of time and status, from work shirts to three-piece suits, from sunbonnets to a fox-fur stole, but ties to the old country pervaded my grandparents’ daily lives in California. They spoke Japanese, ate Japanese-style meals, grew vegetables as they had in Japan, shopped in Japantown, and prayed at the Buddhist temple that they and their fellow immigrants helped build. Whenever times got tough in America—and they did—my grandmother stood on a cliff at the edge of the Pacific and gazed homeward. The emotional pull was so strong that I wondered why they’d never returned.

I was born and raised in the United States, as were my parents. I grew up mainly in all-white neighborhoods, but long stays with my grandmother anchored my identity as a Japanese American. They were the stable warp that steadied the uneven, up-and-down weft of life in America.

My baachans and uncles and aunties passed on a love of nature and a pull towards kindness and gratitude. My heart was lifted by wabi-sabi and chambara movies and illuminated by the simple sight of a ginko leaf and plum branch, soothed by camellia pink and tea green. My father liked to claim samurai lineage, but my blood is alive with dirt farmers, housemaids, and gardeners that felt no need to be anything but their plain-spoken selves.

In 2003, I was going to Japan with a decent Japanese accent, but a three-year-old’s vocabulary. I was nervous about trying to navigate my way to a tiny village on the backside of Japan’s southern island. I’d been shocked and hurt during a layover in 1972 in transit from India to San Francisco. Tokyoites scorned my halting pleas for help with the jumble of subway ideograms. They looked at my Japanese face and assumed that I was a native speaker pretending to be like my gaijin—foreign—companion.

.

Thankfully, thirty years later, I found that Japanese nationals understood that people who looked like them could have been born in other countries. “Amerika-jin dakara, amari wakarimasen (I’m American, so I don’t understand much),” drew quick and sympathetic understanding in tourist-savvy Kyoto, where it was a snap to book fast trains and reserve rooms through English-speaking agents.

So I felt confident as Ben and I stepped off the shinkansen at the Kumamoto train station. We headed straight for the tourist information booth.

“Sumimasen, Itakusu wa doko desu-ka (Excuse me, where is Itakusu village)?” The young clerk was friendly, but her English was worse than my Japanese. She riffled through a phone-book-sized directory and shook her head regretfully. “Sore wa sonzaishinai (It does not exist).”

“Mata mite kudasai. Yamaga ni chikaku (Can you look again? It’s near Yamaga.),” She looked through the directory again. “So-re wa son-zai-shinai,” she enunciated slowly.

How is that possible? I wondered. How could a whole village cease to exist? I visualized houses tumbling into a sinkhole. The clerk conferred with a supervisor who delivered a long Japanese explanation and summed it up in English.

“New system. We cannot help. Record office. Monday.” They both bowed regretfully.

So close, yet so far! Sakuichi’s village had disappeared. Our journey was over before it started. Dejected, we dropped our luggage at the hotel, then strolled through the town, passing an ungainly jumble of concrete offices and residences. A sign with the kanji for “river” led us to the barren footpaths of a river lined with riprap. To my disappointed eyes, the city was a nondescript sprawl with none of the antique and precious charm of Kyoto.

In search of food, we entered a covered arcade crammed with brightly-lit shops hawking jeans and children’s wear and blasting Western music. Fashionably dressed young women bought toilet-seat covers and shower curtains at a giant Hello Kitty store. We ate at a chain restaurant filled with office workers slurping mediocre ramen with their backs turned to each other. So much for conversation and local color.

As we trudged back to our hotel, my travel companion Ben noticed a sign that read ‘John’s Bar.’

“Let’s check it out. The guidebook says it’s owned by a gaijin,” he said. We descended narrow cast-iron stairs to a closed basement door. When we pushed it open, a foreigner’s voice rang out crisply from the dimly lit interior. “Closed tonight. Sorry.”

“We weren’t looking for a drink anyway,” I said, smiling apologetically at a middle-aged man with a neatly trimmed beard and a New Zealand accent. “We just wanted to talk to a foreigner about what it’s like to live in Kumamoto City. Do you have a few minutes to spare?”

He beckoned us in with a cock of his head. He loved Kumamoto City, he said. He’d arrived ten years earlier to study kendo in the home city of fabled swordsman Miyamoto Musashi. Kumamoto was still a world-class center for martial arts, and many champions were members of the city police force. John had married a Japanese woman and become a high school English teacher. The bar was something of a hobby, a gathering place for expatriates, and a venue for his amateur rock band. As a matter of fact, they were rehearsing that night.

Band members trickled in. While they hooked up their amplifiers and speakers, Ben and I talked with Eddy, the vocalist. He was a Japanese civil lawyer who had honed his excellent English during a two-year stint in Toronto. He was intrigued when I explained that we had come to search for my grandparents’ roots.

“What is the name of the village?”

“Itakusu,” I said, “but it seems to have disappeared.”

“Oh, it’s still there,” Eddy said. “Several years ago, the government consolidated small villages into larger townships. Itakusu and Kita-Itakusu are now part of Mikawa town. My wife comes from near there. It’s about an hour-and-a-half away by bus.”

I could hardly believe that chance had led us to a dark, basement dive and a stranger who could set us on the right path. Eddy kept detailed village maps in his car for his work.

“Hey guys,” he called out to his colleagues, “can you practice your instrumentals while I help these folks?” Eddy and Ben went to make color copies of his maps while I marveled that the mall had a copy store open at 8 pm on a Friday. When they returned, Eddy spread out the maps on a table and traced out the route to Itakusu. He even knew the route number of the bus to Yamaga, the nearest large town.

“You’ll have to transfer there. I don’t know the bus number to Itakasu, but someone should be able to help you. And go tomorrow; the smaller routes don’t run on Sundays.”

Thank goodness Eddy had given us the Yamaga bus number. At the terminal, we couldn’t understand the kanji, only the route numbers. When we reached Yamaga, housewives at the bus stop clustered around Eddie’s map and steered us onto the bus to Itakusu. They were intrigued that I was a Sansei whose ojiisan had gone to America ninety years before. They clucked over us like protective hens. Before they got off the bus, they passed my story along to newly boarding passengers who agreed to make sure we didn’t miss our stop.

A woman who got off at the same stop we did pointed to a sprawling concrete-slab building across the street and nodded encouragingly. Ben and I paused to take in our surroundings. There seemed to be no town to speak of. Aside from what looked like a light industrial building and a grocery store, we were in the country. No lodgings or eateries in sight. A wide creek meandered through drab winter fields punctuated by thin scatterings of houses. The woman pointed again towards the big building and shooed us firmly across the road.

There was a sign outside, but of course, we couldn’t read it. It didn’t look like my idea of a government building at all. Hesitantly, we walked inside. At the counter. I explained in English that I was looking for my grandparents’ koseki (family registries). I produced my mother’s 3x5 card and pointed to my grandparents’ names. He asked for my passport and birth certificate and showed them to his supervisor, then tapped into his computer. In about two minutes, the printer spit out two documents printed on blue-flowered paper. “Ojiisan,” the clerk articulated slowly, pointing to the right sheet. He tapped out ¥1500 on his calculator, and then waved to the other paper. “Obaasan.” Another tap on his calculator, another ¥1500. He showed us the total and bowed.

For ¥3000, about 30 bucks, I had the treasure I’d been hunting: my grandparents’ registries. And I couldn’t read a word.

I would have to wait until I returned home for my Uncle Frank’s Japanese wife to translate the scratchy black writing that filled the form’s many boxes. Stunned by how quick and easy it had been to get the koseki, I tottered out of the building, bowing and thanking the clerks who waved as they peeped out from their cubicles.

We still had no clue where my grandparents had actually lived, but I was walking where they once might have walked!

The afternoon was winding down. We knew buses ran every two hours but had no idea when they might shut down for the night. We didn’t have time for serious exploring, so we walked along the creek to absorb as much of the landscape as we could—fallow fields, dry and brown in winter; steep hills thickly forested with bamboo; the shallow, gravel-bedded creek. Most of the houses looked new, with black tile roofs and plaster walls. They were a little bigger than they’d probably been in 1910. The landscape seemed to have changed little, and I thought, if my grandparents had come back again, they probably would have recognized their neighbors’ fields and homesites. It was so heart-achingly beautiful that I could not help but wonder why my grandparents hadn’t returned.

If Itakusu had changed so little, California had changed dramatically during the same period. The fruit orchards and vegetable fields that transformed the Santa Clara Valley in the “Valley of Heart’s Delight” in the early 20th century had been plowed under, never to return. Fertile soil was now covered by asphalt and concrete, transformed into the office parks and glossy suburbs of Silicon Valley.

We had not walked very far when a small car beeped and roared to a stop in front of us. Were we trespassing, I wondered? No. The town clerk leaped out of the car with a smile and explained in a mixture of English and Japanese that my grandfather’s koseki was incomplete. He exchanged the earlier one for a more accurate version.

Before heading back to work he asked, “Doko ni iku no (Where are you going)?” I shrugged. “Just for a walk.” He nodded and pointed farther upstream. “Kita-Itakusu.”

We walked about a half-mile, past more fields and small clusters of houses. My great-grandmother was from here. Our luck had been good so far; would it bring me even closer to my family?

Before I left, my mom had remembered the name Moka Tsutsumi, Sakuichi’s mother and my great-grandmother. She died in 1948. Would we be able to find out something about her?

I asked an elderly woman we encountered. “Moka Tsutsumi oboetemasu-ka? Go ju go-nen mae shinda (Do you remember Moka Tsutsumi? She died in 1948.).” She shook her head and backed away. Was it from my bad Japanese? Maybe, but it didn't deter me. I asked a balding old man in rubber boots hoeing his field.

“Ah, so desu-ne,” he nodded, “asoko ni sunde imashita.” He pointed back towards a cluster of houses we’d passed. My great-grandmother had lived there, he said.

We were on our way to that area when the old man roared up on a motor scooter. He explained excitedly that the man who had taken care of my great-grandmother had just driven by in his pickup and would wait for us in his front yard. The old man waved away our thanks and scootered back to his field.

Shogo Tsutsumi was indeed waiting outside his house, a tall, serious man with a thick shock of hair. He invited us inside, apologizing for not remembering a word from the English classes he’d taken. As his wife served tea and senbei, he pointed to the large, elaborate butsudan in a corner alcove. Photos of his parents and Moka held a place of honor on the Buddhist shrine. Centered above the living room doorway was an oil painting of Moka in formal black kimono with crests on the sleeves.

Despite the common surname, Shogo explained, he and Moka were very distant cousins, not closely related. But his father and my grandfather had been dear friends and neighbors. Shogo’s father had agreed to care for Moka in exchange for the family’s small parcel of land. He explained that Sakuichi and Umematsu sent money when they could, and when Moka grew too old to live alone in her own house, Shogo enlarged his house so she could live with them.

He rummaged in a closet and brought out some ancient photos of Moka and my grandfather. He seemed embarrassed that the images were curled and mildewed. I recognized almost all of them. Our family had copies in America. Like most Issei immigrants, my grandparents sent portraits home regularly, and they preserved the photos they had received in return, solemn portraits of kimono-clad strangers whose names and relationships had died with my grandparents.

We had not finished our tea when Shogo’s wife appeared with another tray, laden with coffee and sliced fruit. I hadn’t expected to meet anyone in Itakusu who remembered my family, so hadn’t brought omiyage (visiting gift). I tried to apologize for my rudeness, but Shogo and his wife looked at us blankly. We’d exhausted our shared vocabulary, so we sat on the tatami and grinned at each other awkwardly.

It was nearing dinnertime and we had to catch the bus. As we made our farewells in the yard, Shogo asked if we planned to visit Moka’s grave. He pointed to the Buddhist temple on the far side of town. No, I told him. It was getting late, and we were afraid we’d miss the last bus. It occurred to me that I was committing another serious breach of etiquette by not visiting the gravesite, but the Japanese phrase “shouganai” came to mind. There was nothing that could be done about it.

As we left, I heard Mrs. Tsutsumi say to her husband, “They didn’t take the photos.” I groaned inwardly. I thought they were simply showing us the photos, not gifting them. I pretended I hadn’t heard, thinking it was best to leave before I committed any more stupidities.

As Ben and I walked back to the bus stop in the gathering dusk. I felt embraced by the kindnesses offered again and again by the many strangers who’d helped me find my grandfather’s home. With a full heart, I soaked in the forested hills, the thatched houses, the river meandering through the fields—it was the very picture of the furusato village, the old home that Issei immigrants longed for.

As the bus wound its way from one mountain valley to another, I tried to envision my grandfather’s journey along this route. When the hills opened out to the broad plains, high mountains, and prosperous farms around Yamaga, I realized what drew him to California. The wide, rich valley around Yamaga resembled San Luis Obispo, where my grandfather established his first farm. He must have thought he’d died and gone to heaven when he went from a tiny plot in Japan to a share in a 50-acre farm within five years of arriving in California. By the time he died from an auto accident in 1934, he was one of the county’s largest growers, raising peas, beans, broccoli, lettuce, and cabbage on 140 leased acres. He did not live to see my grandmother lose it all when the family was incarcerated after Pearl Harbor.

When I got home to California, I showed the family registry to Uncle Frank’s wife, who’d been born and raised in Japan. “This lists father, mother, and siblings going back several generations: ‘farmer, farmer, farmer’….”

“And what’s this blank here?”

“That’s for your grandfather’s father’s name.”

“But it’s blank.”

“Yes.” She didn’t look at me.

“You mean…”

“He was illegitimate.” She bowed her head. “This is a very bad thing. Don’t tell my family.”

“But it’s no big deal anymore.”

She gripped both my wrists and squeezed hard. “Don’t. Tell. Frank. Don’t. Tell. My Children. Please.” She took a breath. “When Frank asked me to marry him, I had to check the koseki to make sure there was no disease or other family problems. So I took the train from Tokyo to Kumamoto. It was 1947; the war had only been over for three years and it wasn’t easy to travel. But I got the koseki. When I saw the blank, I was shocked. I didn’t tell my family—it was such a big disgrace! But I loved Frank, so I married him anyway. I kept the secret all these years. Now you must keep it.”

I did keep her secret, until she and Uncle Frank died. Then, I told my cousins.

“What’s the big deal?” they said, just as I knew they would.

The blank square on the koseki was the last piece to Sakuichi’s puzzle. Land and opportunity drew him to California. Illegitimacy kept him from going home again. But the enduring support of those he left behind lives on in Moka Tsutsumi’s portrait, gracing Shogo’s living room almost a century after Sakuichi left home.

My grandfather fled the poverty and strictness of Japan for American possibilities, but his legacy in both countries is the understanding that, day-to-day, no matter where you are, kindness matters.

When I got home to California, I showed the family registry to Uncle Frank’s wife, who’d been born and raised in Japan. “This lists father, mother, and siblings going back several generations: ‘farmer, farmer, farmer’….”

“And what’s this blank here?”

“That’s for your grandfather’s father’s name.”

“But it’s blank.”

“Yes.” She didn’t look at me.

“You mean…”

“He was illegitimate.” She bowed her head. “This is a very bad thing. Don’t tell my family.”

“But it’s no big deal anymore.”

She gripped both my wrists and squeezed hard. “Don’t. Tell. Frank. Don’t. Tell. My Children. Please.” She took a breath. “When Frank asked me to marry him, I had to check the koseki to make sure there was no disease or other family problems. So I took the train from Tokyo to Kumamoto. It was 1947; the war had only been over for three years and it wasn’t easy to travel. But I got the koseki. When I saw the blank, I was shocked. I didn’t tell my family—it was such a big disgrace! But I loved Frank, so I married him anyway. I kept the secret all these years. Now you must keep it.”

I did keep her secret, until she and Uncle Frank died. Then, I told my cousins.

“What’s the big deal?” they said, just as I knew they would.

The blank square on the koseki was the last piece to Sakuichi’s puzzle. Land and opportunity drew him to California. Illegitimacy kept him from going home again. But the enduring support of those he left behind lives on in Moka Tsutsumi’s portrait, gracing Shogo’s living room almost a century after Sakuichi left home.

My grandfather fled the poverty and strictness of Japan for American possibilities, but his legacy in both countries is the understanding that, day-to-day, no matter where you are, kindness matters.

Shizue Seigel is a third-generation Japanese American who explores complex intersections of history, culture and spirituality through prose, poetry and visual art. She’s a long-time San Francisco resident who’s never quite hung up her traveling shoes. She grew up an Army brat in segregated Baltimore, Occupied Japan, California farm labor camps and skid-row Stockton, and has explored the diverse worlds ever since. As founder/director of Write Now! SF Bay, she supports writers and artists of color through workshops, events and anthologies. Her eight books include five Write Now! anthologies, most recently Uncommon Ground: BIPOC Journeys to Creative Activism.

www.WriteNowSF.com. www.shizueseigel.com. https://facebook.com/shizueseigel https://www.instagram.com/writenowsfbay/

www.WriteNowSF.com. www.shizueseigel.com. https://facebook.com/shizueseigel https://www.instagram.com/writenowsfbay/

Use and/or duplication of any content on White Enso is strictly prohibited without express and written permission from the author and/or owner.

Table of Contents Next Page

Proudly powered by Weebly